A million imaginary friends

We surveyed 1,000 parents of 3 to 10-year-olds to discover how many imaginary friends exist across the UK today

- 17% of children have an invisible companion, with six in 10 taking a human form

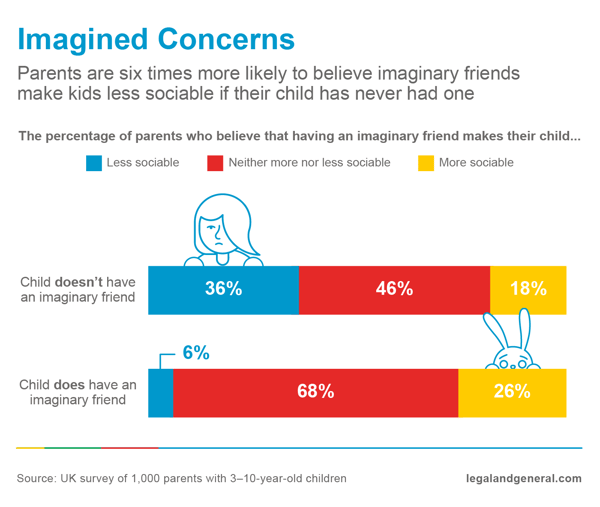

- One in three parents thinks an imaginary friend would hurt their kids' social skills, but parents whose children have pretend pals are six times less concerned

- 75% of parents feel their child is now more creative thanks to their invisible friend

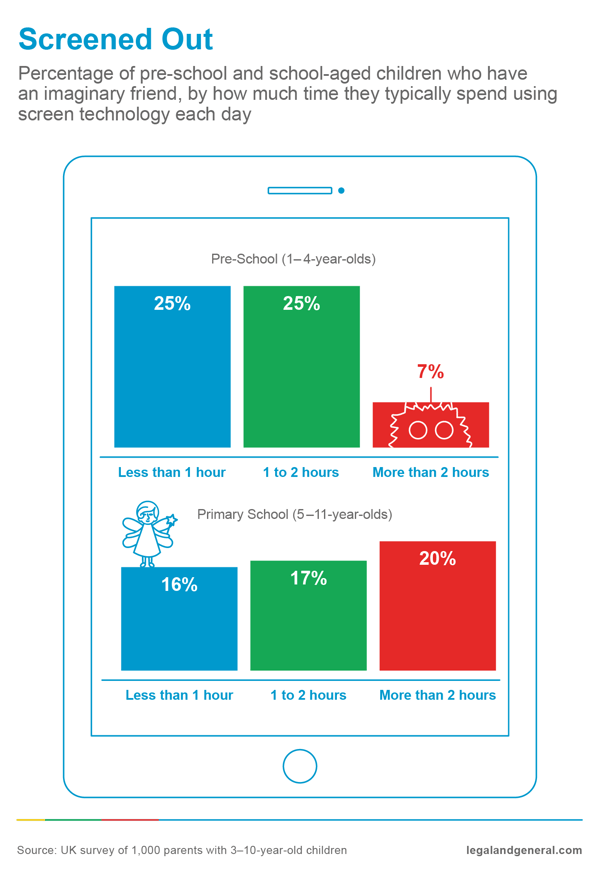

- Kids aged 1 to 4 who use screens for less than one hour per day are 3.5 times more likely to have an imaginary friend than those with more than two hours screen use per day

Try visualising everyone who lives in Birmingham standing shoulder to shoulder in a heaving crowd that stretches a kilometre into the distance. Instead of real people, imagine each person is a different fantastical creature, from mermaids and lions to robots and dragons. This gigantic cast of characters represents every imaginary friend that exists in Britain today. There are at least one million in total, of all shapes, sizes and species, each one conjured up by the creative mind of a 3 to 10 year-old child. We know this because 17% of 1,000 parents we surveyed said their child currently has a fictional playmate.

We discovered what the nation's imaginary friends look like, how they differ between children and whether technology is threatening their existence.

When do children first create imaginary friends?

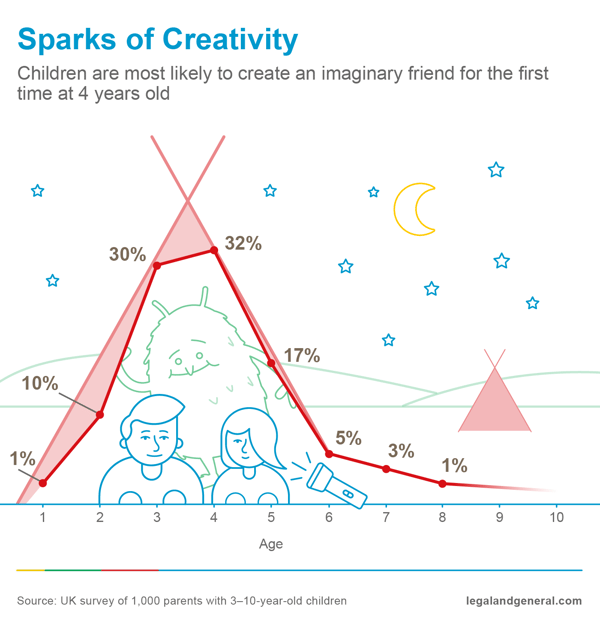

Our survey included 1,000 parents of 3 to 10-year-olds. Imaginary companions aren’t restricted to this age range, but our results show that 99% appear by the time the child is 10-years-old. The most common age a child dreams up an imaginary companion is four. It’s at the 4 to 5 year-old mark that kids develop greater independence, language skills and creativity – vital ingredients for the introduction of an imaginary friend.

However, imaginary companions haven’t always been seen as an expression of positive personality traits. Before the 1960s, some children were discouraged from having imaginary friends because researchers believed they revealed an inability to separate fantasy from reality and might even be a sign of mental illness. Since then, scientific thinking has radically changed. It’s now thought that ‘rehearsing’ conversations and interactions with imaginary friends can help children improve their social skills and expand their creative thinking.

Based on our results they’re also commonplace – on average, 17% of 3 to 10 year-olds currently have an imaginary friend, and by the age of 10, there’s a 37% chance a child will have had one.

When we asked parents how they felt about imaginary companions, their concern differed depending on whether their child had ever had a fictional friend. Among parents of children without imaginary friends, 50% said they would be at least ‘slightly concerned’ if their child told them they had one. Among parents of children with imaginary friends, only 21% expressed concern.

Parents’ apprehension might depend on what type of invisible friend their child is encountering as there is a big difference between a fluffy little squirrel and a monster under the bed, which could be a sign of anxiety.

Over 50,000 imaginary unicorns roam the UK

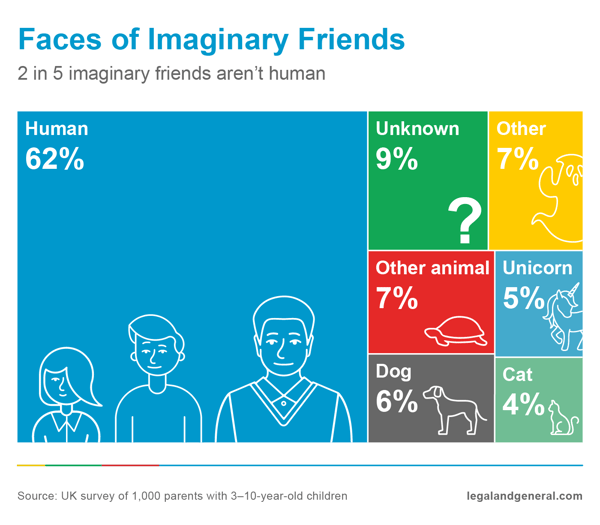

Six out of 10 imaginary friends are human, while the rest are a mix of animals and other creatures. Unicorns are more common than cats and only slightly less common than dogs. Girls are 2.5 times more likely than boys to have an invisible unicorn as a friend (10% vs 4%).

Among the 8% of imaginary companions that weren’t people, animals or unknown personalities, there were ninjas, trains, aliens, skeletons, and many miscellaneous monsters. Some parents didn’t know what species their child’s imaginary friend was. ‘Not sure – he lives down the plug hole’, said one mum.

From pocket monsters to invisible behemoths

Most imaginary friends are human, and just over half are the same physical size as the child imagining them. This makes sense when we think about the role of imaginary friends as playmates and peers to children, walking and talking with them wherever they go.

41% of the parents we surveyed said they were aware of their child playing with their imaginary friend at least once per week, and 26% said at least once per day, which suggests an ongoing friendship similar to that of a real child.

Pretend companions that were smaller than the child imagining them were typically animals like monkeys, rabbits and birds. Larger examples included bears, horses, wolves, dragons, and Beast (from Beauty and Beast). Girls were more likely than boys to have companions that were smaller than them (34% vs 24%) and they were also less biased towards the gender of their fictional friend.

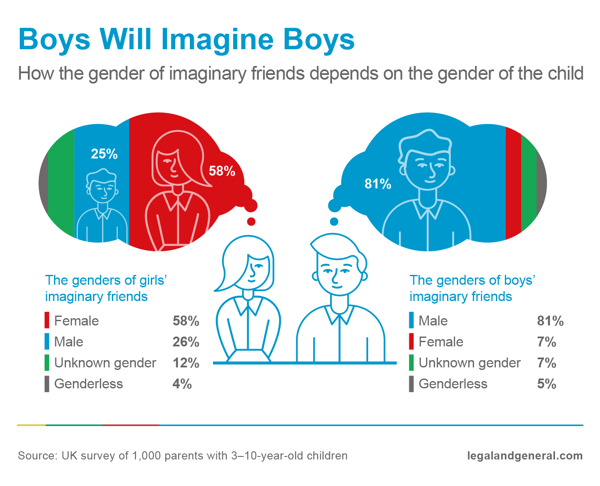

Girls are more likely to imagine friends of the opposite sex

Girls are 3.5 times more likely than boys to have an imaginary friend of the opposite sex. Specifically, 81% of boys’ imaginary friends share their gender, compared to 58% of girls'. One possible explanation is that the role of invisible characters in the lives of young girls is slightly different to boys. For instance, 54% of girls show parenting behaviour towards their invisible character compared to 37% of boys. Examples include checking the friend is wearing their seat belt, helping them safely cross the road, and teaching them how to brush their teeth.

Girls are also slightly more likely to say that their imaginary friend sometimes protects them. ‘She told me Catboy watches over her while she sleeps’, one dad told us. Several parents said their child’s invisible friend wards off other imagined monsters, especially at night and during bad dreams.

On average, one in five parents said their child had blamed something they did on their imaginary friend, with boys being a bit more likely than girls to pass the buck to their imaginary pal. For example, ‘He ate two packs of crisps and claimed his friend had one’. One in 20 parents, equal to around 50,000 parents nationally, said their child had reported that their imaginary friend had forced them to do something against their will. ‘She drew all over the walls but said she had no choice – her friend made her do it’, one parent said.

Perhaps it’s imagining such scenarios, in which their children tell tall tales and shift responsibility, that makes some parents think imaginary friends are a recipe for antisocial behaviour. However, this belief appears to significantly change once a parent has witnessed their child interacting with an imagined playmate.

Imaginary friends don’t harm children’s social skills

It seems that parents sometimes have overactive imaginations just like their children. One in three mums and dads whose kids have yet to have an imaginary friend thinks having one would make their child less sociable. However, among parents who have seen their children interacting with invisible friends, less than one in 10 shared this concern.

One in four parents felt their child was more sociable thanks to their interactions with an imaginary friend, and 3 out of four said their child was more creative.

Just as adult friendships can run their course as circumstances change, kids’ relationships with their invisible playmates gradually fade as well. 14% of imaginary friends are around for three to six months, 27% last for six months to one year, and 25% survive one to two years. Only 6%, equivalent to 60,000 of today’s fantasy friends, live longer than three years.

Imaginary friends aren’t the only invisible characters children believe in. In fact, some of the most widely believed beings aren’t the creations of children at all.

Belief in mythical beings starts to drop around age six

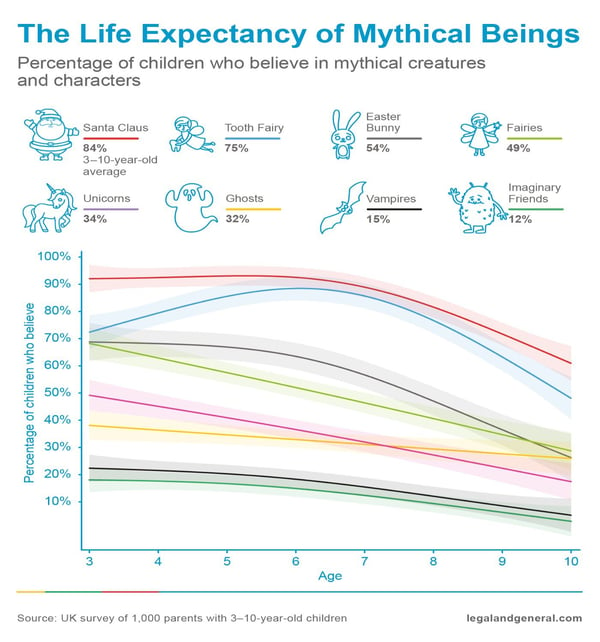

Some mythical characters could be considered ‘institutionalised imaginary friends’, with hundreds of millions of children (and probably a few grown-ups) firmly believing they exist. Santa ranks highest among 3 to 10 year-olds, with an average of 84% believing he exists. The level of belief in Santa is just over 90% from the age of 3 to 6, then falls each year after that. At the age of 10, belief in Santa has dropped to 61%.

Belief in the Tooth Fairy conveniently rises and falls with the need for a mutual agreement between child and parent to swap baby teeth for coins under pillows. Ghosts are a little different, however. Of the seven widespread mythical creatures and characters we polled parents on, the belief in ghosts among kids was the most consistent, ranging from 38% at the age of 3 to 26% at 10. Interestingly, some parents we spoke to believed their children’s imaginary friends were evidence of the afterlife.

‘My youngest son used to talk about when he was here before he was born. I think as children grow older, many adults tell them there's no such thing as an imaginary friend, so the barriers eventually come down and they switch off to being open to spirits’.

Children who believe in various mythical characters are more likely to have imaginary friends. Kids are 46% more likely to think unicorns are real if they’ve had an invisible companion, and 28% more likely to believe fairies exist.

Imaginary friends are often dreamt up from scratch, whereas Santa, vampires, the Easter Bunny and the Tooth Fairy can all be seen in films, TV shows and books, which explains why belief in them is more widespread. But is the use of digital devices to watch shows at any time and in any room or situation stifling kids’ imaginations and elbowing out their imaginary friends?

Prolonged screen time can squeeze out imaginary friends

In the past, the presence of an imaginary friend signalled a problem with a child. Today, we’re more likely to worry that the absence of an imaginary friend is a sign that a child’s creativity and self-directed play haven't developed properly, possibly due to an overreliance on passive forms of entertainment, such as phones, tablets and TV. Our previous research showed that 32% of children have their own phone before they’re 9, and 65% have their own tablet.

Based on our results, there does appear to be a relationship between screen use and the prevalence of imaginary friends, but it’s not as simple as saying ‘Technology is killing imaginary friends’. We only noticed the effect among very young children. Pre-school children (1 to 4 years old) who use screens for less than two hours a day were 3.5 times more likely to have an imaginary friend than those who use screens for more than two hours a day.

As children get older, screen time has less of an effect on the likelihood that they will have an imaginary friend. Among primary school children (five to 11-years-old), 16% of children who spent less than an hour a day on screens had an imaginary friend compared to 20% of those who spent more than two hours using a screen. This suggests that technology can have a negative impact on the creativity of younger children, but that the effect lessens as they get older. This result is backed up by previous research showing that children with heavy use of television, video games and computers scored worse than those with light use on tests of visual memory, attention span and – the crucial faculty used to dream up imaginary friends – creative imagination.

Summary

The one million imaginary friends in the UK are a diverse crowd. From humans, to animals and mythical beings of all shapes and sizes, the varied forms imaginary friends take show that imagination in today’s young children is alive and well. Parents can feel comforted by the accounts of others who have seen their child grow alongside invisible pals without slowing their social development.

However, parents looking to foster creative play in their children should note that the age when imaginary friends are most abundant is when screen technology is most likely to stifle their child’s inventiveness, by limiting the child’s opportunity for unstructured play. The solution is not to cut technology out altogether – limiting your child’s screen time to less than two hours a day could help keep a seat free at the kitchen table for their imaginary friend.

Methodology

We surveyed 1,000 British parents with a child aged three to 10 in November 2018. We asked them whether their child has an imaginary friend, to describe the appearance and character of that imaginary friend, how their child engages in other forms of imaginative play, and what factors they think make their child more or less likely to have an imaginary friend. Each survey respondent focused on only one child. If they had more than one 3 to 10 year-old child, they focused on the child who had the imaginary friend they could describe in most detail.

Fair use statement

Feel free to share our findings with your friends (real or imaginary) for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you link back to this page to give our research team credit.

Why life without insurance is no fantasy

There might be no such thing as the tooth fairy, but the risks of not getting life insurance are all too real. With financial back-up in hard times, you can focus on creating a safe, secure environment where your little one’s imagination can run wild. You won’t need to cover their unicorn, but the greater your protection, the greater your peace of mind. Take a look at our family life insurance guide for more details.

Sources

https://www.webmd.com/parenting/4-to-5-year-old-milestones#1

http://psychology.tcd.ie/spj/past_issues/issue02/Reviews/%286%29%20David%20Lydon

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28707060

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/growing-friendships/201301/imaginary-friends

https://www.legalandgeneral.com/life-cover/confused-about-life-cover/articles-and-guides/screen-time-left-to-their-own-devices